How many and how people die,

.. it's complicated.

More to the point, just figuring out which data sources you can trust for this kind of information is trickier than I would have thought.

I asked you about your intuitions, and before I did any research on this, I wrote down a few of mine:

A. What fraction of people die from car accidents?

B. How many people die from other kinds of accidents?

C. How many people die of different medical conditions?

D. What are the leading causes of death?

My guesses, before having done any research:

A. Car accidents: 15% of total deaths / year

B. Other (non-car) accidents: 5% / year

C. Medical conditions (not including old-age): 50%

D. Leading causes of death (of any or all causes), in order: Accidents; Heart problems; Cancer

Let's see if we can answer these questions:

1. How many people die (from all causes) each year in the United States?

2. What are the top 5 causes of death in the United States? (As a fraction of the whole.)

As I mentioned, the interesting question is going to be: Where do you get your data from, and why do you believe it's accurate?

The obvious queries on different search platforms gives different numbers. There's variation in the answers even within a single search platform. Compare these results with slightly different queries on Google:

Notice that there's a 250,000 person difference between these two numbers. Why? Because they come from different sources. The first query gives a webanswer from a webpage at www.medicalnewstoday.com (which in turn gets its data from the 2014 CDC numbers), while the second query shows an answer that's from Quora.com with data from the UN data source, UNstats.un.org, and these numbers are from 2008.

Oddly, the first article tells us that the CDC data is no longer available. The link Medical News Today cites IS broken, but the obvious query:

[ CDC 2014 data deaths ]

If you click on the Quora link in the second query [how many people die each year in the us], the writeup there takes you to the UN demographics report from October 2017, which tells us the total number of deaths for 2015.

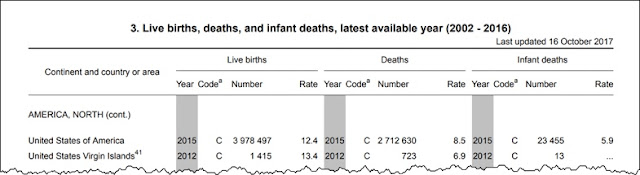

Looking at that page you see the entry for the US:

READ CAREFULLY: The Quora article says that "the most recent data available is from 2008." But this data is from 2015 (the date is in the gray column), and the report was updated on 16 October, 2017... but notice that the number shown here is different from what's in the summary! Here, the UN says it's 2,712,630 deaths in 2015. As opposed to the 2,473,018 deaths reported in the 2008 UN summary seen in the webanswer. Notice that we're comparing deaths in 2008 vs. deaths in 2015--of course there's a big difference.

Think about what this means: Of course, you'd expect the total number of deaths to change year-by-year: the overall population increases year-by-year, and the death rate changes as well... just much less than the overall growth in population.

Okay--so can we find the CDC data from 2015 to be comparable with the UN data?

I noticed that in the CDC report we found above, the actual text in the paper was this:

"In 2014, a total of 2,626,418 resident deaths were registered in the United States..."

I know that these kinds of reports are often written from a template. (That is, they probably just copied the report and plugged in the new numbers for 2015.) So I did this query to find the report for 2015:

[ "In 2015, a total of * resident deaths" ]

Notice that I changed the year to 2015 and used the * operator to match the new number for that year, and I double-quoted the whole thing to find a match for this exact phrase.

Voila! That takes me directly to the CDC report for 2015 where we find out that " A total of 2,712,630 resident deaths were registered in the United States in 2015."

Let's compare these numbers from CDC and the UN:

2014

UNC 2,626,418

CDC 2,626,418

2015

UNC 2,712,630

CDC 2,712,630

Notice anything odd about these numbers? They're exactly the same! If you go back a few years, you'll see more of this pattern. Which makes me wonder: Where does the UN get their numbers? From the CDC! (After looking around, I found that nugget in a footnote, of course.)

Which means that although we've "double sourced" this data, it's actually NOT double sourced--the UN is just taking whatever data the CDC hands them.

You might be tempted to think that the UN is getting their data from a different US source; after all they give their data citation as coming from the "U.S. National Center for Health Statistics" in their "National Vital Statistics Report." But when you look up the NCHS, you discover that they're a department of the CDC. It turns out that they're the people who collect the data in the CDC!

This is an interesting insight: the simple question How many people die each year in the United States? turn out to have a more complicated answer. It varies by year, and as you might imagine, it varies depending on how you measure it.

WHAT? Isn't a death a death? Can't you just count death certificates?

Well, yes, but are you also counting people who disappear? What about US citizens that die overseas? Are they listed as a US death, or as a death in that country? Are you counting from January to January, or just one month-long period and multiplying by 12? Are abortions counted as deaths? Stillbirths? What about people in Puerto Rico, the US Virgin Islands and other territories? (Why are the Virgin Islands broken out into a separate line item in the CDC report?) What about military deaths in non-US locations?

As often happens, once you start digging into a research question, you learn a lot about the area. You learn the little details about your question that deepen your understanding of the question you're asking. This happens all the time when we do our SRS Challenges: What starts out as a simple question turns into something larger and with more nuance than you thought at the start.

In each of the questions I asked above, you can find the answers in the data commentary that's usually at the bottom of the data set. (Sometimes it's scattered around in the text itself.) But it looks like this, usually presented as footnotes:

The notes describe the properties of the data: in this case, footnote #36 tells us that military and US civilians who die outside of the country are NOT included in the totals.

In this case, we found out that which year you're asking about makes a big difference.

What about that other question, causes of death in the US?

Those same reports also break down the causes by percentages of all US deaths. From the

CDC report on health issued in 2017 (with data from 2015), we find that the top 5 causes of death in the US are:

1. Heart disease (23.4%)

2. Cancer (22.0%)

3. Chronic Lower Respiratory Disease (CLRD) (5.7%)

4. Accidents (5.4%)

5. Strokes (5.2%)

They illustrate this nicely with this chart (from the previous CDC reference):

|

| From CDC report, "Chartbook on Long-term Trends in Health" pg. 18 |

As you can see, heart disease and cancer are the two largest causes of death, accounting for 45% of all deaths in 2015. CLRD, the next most common cause, is only around one fourth as much.

When I look back at my guesses (at the top of this post), I see my intuition was really wrong. Accidents of all kinds are around 5.4% of the total (which means that car accidents are less than that).

We may worry about mass murders or the latest version of flu, but the big killers each year are heart disease and cancer. They are much more significant in terms of public health than anything else by far.

When you look at the causes of death over time, it's a fascinating piece of data:

|

| Same source as above. Notice that the Y-axis is a log scale, which means that a little big of change coming down (e.g., heart disease or stroke) is actually MUCH bigger than it might seem. That decline looks much less than it really is. The improvement over 40 years is amazingly good. Note also that CLRD is a new disease label that combines asthma, bronchitis, emphysema. In 1999, the disease coding system changed to recognize those diseases as a cause of death, and separated out pneumonia and the flu into a separate category. |

What is so striking is how constant many of these numbers of deaths are: Why do roughly the same number of people die each year in accidents?

This chart also has good news / bad news: We're getting better at managing heart disease, but the overall cancer rate hasn't changed much in 40 years.

And of course, another big factor in the causes of death is age at time of death. People die of very different causes at different ages. I saw a data table that suggested this, so I did the search to see if I could find a summary chart.

[ site:cdc.gov causes of death by age ]

and found this chart in the CDC chart collection for causes of death, which shows how people die for very different reasons at different ages. While cancer and heart disease are the largest causes of death, they come into play only after age 44. Before 44, you're more likely to die of an accident.

Search Lessons

1. When looking at data, be SURE you understand WHEN it was collected and WHAT it's measuring. As we saw, different sources (Alpha vs. Bing vs. Google) all draw on slightly different resources from different times. This makes a big difference.

2. Consider other factors that might influence your data. In this case, death rates vary a LOT by age. (They vary by other factors too, such as gender, race, and location--but I just focused on age in this post.) Be sure you understand all of the aspects of the data that are important to you.

3. When you need the "next document in the series," remember that those documents often use boilerplate language, which you can find with a fill-in-the-blank query, like [ "In 2015, a total of * resident deaths" ]. This is an amazingly handy trick to remember.

4. Be sure you know where your data comes from! I naively thought that the UN would have different data than the CDC--but noticing that their numbers are all the same drove me to check where the UN data came from... and it was... the CDC. This data is NOT truly double-sourced!

Search on!

(I'll post a bit of background about why this one took so long to write up in my next post, later this week. Let's just say travel go in the way. And... I'll put out a new Challenge on Monday. Stay tuned!)