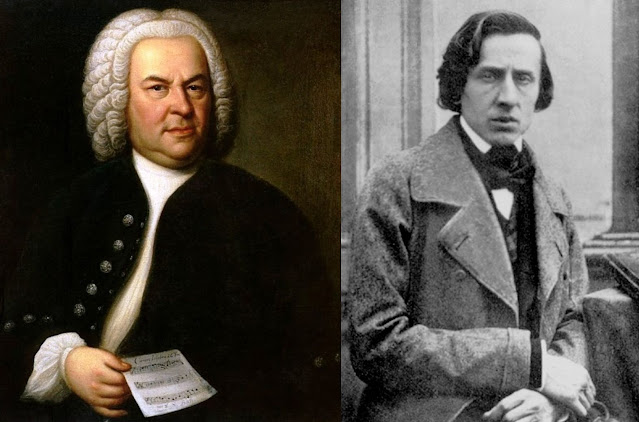

In the pre-dawn quiet, somewhere on the north coast of California, I looked up into the soft, cold, gentle mist…

|

| Rainy day on the Northern California coast |

... letting it play over my face. It’s a reflective gesture, especially on New Year’s Eve when all of the year is worth rethinking. Rain has fallen since the dawn of the Earth, and I’m just feeling the latest cycling of water from sea to sky to land back to sea. But it puts me in a deeply contemplative state of mind. What happened this year that was different from the year before? How can I make next year even better? What have I learned?

You might wonder about all of those questions, but as I lifted my face to the sky, I could feel each tiny raindrop strike my cheeks—a kind of constant spray where each pinpoint of rain registered—dot.. dot.. dot.. dot..—quietly making every point of my skin register a tiny scintilla of cold and wet. You might think of this as a kind of celestial scanning of your inner self, the rain gods probing every square millimeter of your face and your life. It felt a bit like video static on my skin.

It felt like that image of William Gibson in Neuromancer, “The sky above the port was the color of television, tuned to a dead channel.” I realize that there are people who have never seen the black and white video static of a dead television channel. For you, here’s a YouTube video. https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=ubFq-wV3Eic (It’s a handy concept to have—the rapidly alternating pixels of black and white, rapidly flipping in a random order, flickering chaos. I don’t quite know how to convey that sense in words—video static as a phrase will have to do.)

But the thing that popped into my mind was this: I feel as though the droplets are tiny and rapid and random and dense, but I also know the spatial resolution of touch on the skin of my face is pretty low. So how can I feel as though I’m in a shower of tiny video static droplets? And while I’m thinking about that, I also start wondering how I can feel the cold of each droplet as it splashes down. How fast are my cold receptors? Can I actually FEEL each of those tiny droplets as a touch and as a chill, or is my perception a kind of synthesis of all the drops over a short period of time? How much of my perception is accurate and how much is just made up by my sensory system?

A psychologist would call this a question of veridical perception—that is, the direct perception of stimuli as they exist in the world. Am I actually feeling what my perception actually indicates, or does my nervous system do a kind of quick extrapolation from the perceived reality to create the sense of video static on my skin?

Naturally, I then spent a couple of hours doing a bit of research into the spatial resolution of touch. Doing the obvious queries on Google and reading widely in neuroscience and perception. I learned about the “two-point discrimination test” [1], and that we have different receptor neurons for heat and cold, yet again different receptors for touch and different ones for touch, different ones for stretching, and different ones for sensing vibrations. Fascinating stuff, but in the end, I had to do my own two-point discrimination test on my face to determine what the spatial resolution is on MY face. After using an incredibly sophisticated two-point testing device (that is, a paperclip I bent into parallel arms whose distance I could vary) I found that my cheek can tell touchpoints that are around 6 mm apart—around 0.25 inches. This means that my face can only register drops that are 6 mm apart from each other. Since my face is around 254 mm wide (assuming a circular face), I can really only feel around 42 different droplets from one side to the other. On the other hand, my lips can determine one- versus two-points with only a 1mm separation, so my face is at different spatial resolutions!

But that’s not the way it feels. I can't feel the difference in resolution--it's all of one piece. I would have naively guessed that I could uniformly detect 100 drops of rain from cheek-to-cheek. The pattern of rain certainly feels that way as the rain washes across—it feels like a fairly dense spray of droplets—I would have thought I should feel at least 1000 droplets as the morning rain falls from heaven.

And what about the cold? A little more research tells me that cold receptors are even farther apart, and much slower to react than touch. So, the sense I have of small cold drops hitting my face in a dense, random pattern can’t possibly be accurate. The rain is cold, certainly, but when the drop hits my skin, I register the drop’s strike, and the cold perception comes much later, probably right around the time another drop hits the same point.

Once you start thinking about this, you also have to wonder—what is the composition of rain? Are all drops the same size? I noticed in the heavier rain that came later that there were also lots of little drops as well. Are they shards from collisions of large raindrops, or did they never get merged into a big drop?

Questions, always questions.

This year I’ve spent a lot of time writing my SearchResearch posts—more time than I’d care to admit, but it’s worth it. The process satisfies this deep inner itch I have--I want to understand the world.

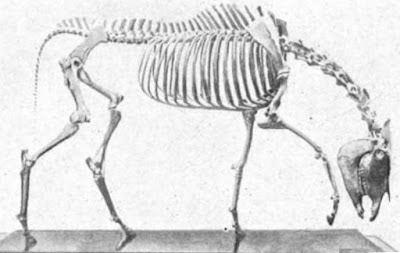

The nature of my curiosity is to constantly ask “Why?” It’s an everpresent question that’s always on the periphery of my lived experience. This year I walked through a park and thought “why is there an odd, flat space in the middle of the park?” Or, seeing gnats swarming on the beach I wonder “Why do they do that?” Seeing a horse in a nearby meadow leads me to recall from an adjacent memory about horses that while there are horse fossils in North America, and yet there were no horses here when the Europeans arrived: Why?

Curiosity is more than just asking random Why questions—it often builds off of something else you know. In the park, there were no other flat places like that one—it just looked wrong: Why? In the case of the beach gnats, I saw them all over the beach, but it wasn’t one giant beachball of swarming gnats, but several gnatty swarms in different places. To ask the Why question about horses, I had to know that in 1492, there were no native horses in North America, and that there were horse fossils littering museums all over. Why?

|

| Horse fossil from the La Brea tar pits in Los Angeles; Miocene. |

Asking curious questions means noticing something about the world; it means knowing something is out of place, doesn’t fit, or doesn’t agree with another thing you know, or recognizing that you really don’t know how something works. Then, ask that question, follow-up with a bit of looking.

Fortunately, we live in a time where online resources let us do a bit of desk research and find the answers to these curious questions.

What questions will you ask in the year ahead? What role does innate curiosity play in your life?

-- Curiously yours

-- Dan

==

1. That is, how far apart do two points have to be on your skin before you feel them as two points rather than one? Answer: it varies widely, from 1 mm at the fingertip to 40 mm on the skin of your thigh). I also learned that a “receptive field” is the region that’s sensed by a touch receptor. For more details: http://www.scholarpedia.org/article/Receptive_field