When do you use one tool versus another...

... that's the basic question: "When do you use regular Google versus LLMs for what types of research questions. How do you know when to use each?"That was the Challenge:

1. How do you know when an LLM AI system will give a good answer to your question? How would you characterize a research question that's really good for AI versus a research question that you'd just use a "regular" search engine for?

I think what I'm looking for is a clear description of when an AI is most likely to give an accurate, high quality answer? By contrast, I think I know how to say when I'd use a search engine, but it's harder to describe the kinds of questions that I think an AI would do poorly.

I’d like to be able to tell my student what and when I’d use one tool over another when asking SearchResearch questions. Here’s my summary…

A. When would I use a regular search engine?

Use a search engine when you need facts, sources, and current information.

If your question is a navigational one (finding a particular web site), or is a "what," "where," or "when," then a regular search engine is what you want.

1. Navigating: When I’m either navigating to a site that know exists (Example: [movie theatre near me] or [auto repair Palo Alto] )

2. Current events: Sometimes you want the latest information or updates on something. You’re usually better off using a search engine since they are constantly updating their index. Often the information will be crawled within a few minutes of your query. This is particularly important for current or breaking news. (Example: [brush fire near San Jose CA])

3. From a particular source: Often I’ll want information from a particular source (usually a source I know and trust). That’s when using the site: operator is incredibly useful. This is one of the true strengths of a search engine. (Example: [site:nytimes.com crypto industry] for articles about crypto from the New York Times.)

4. A particular kind of result: The search engines have specialized tools for finding images, data sets, books, travel information, news, and maps information. While you might be able to get your favorite AI to give you travel directions, I think you’d be MUCH happier with a dedicated mapping app or service like Google Maps.

Overall, there are still a LOT of cases where using a specialized tool is going to work much better than using a generic AI. You, as an expert SearchResearcher, need to know what those tools are, what they're called, and how to use them.

In other words... you still need to know stuff....

B. When would I use an LLM / AI system?

LLMs are really good at tasks that can leverage their vast text training, pulling in language and concepts from many different places and stringing them together. They are really pretty good at answering open-ended questions that require synthesis across a number of information resources.

In some ways, LLMs are good at a large number of the SearchResearch Challenges. A good deal of what we cover here in SRS is how to find information that’s scattered everywhere and pull it together into a coherent whole. That’s a large part of what my book The Joy of Search is all about. (And, incidentally, that’s why I don’t think there will be a Joy of Search Part 2. Maybe a Joy of AI Research?)

Remmij pointed out that the multimodal AIs are pretty good at describing an image, and often very good at identifying what’s in the image. (Although they’re not perfect: check for yourself.)

And, to paraphrase Henk van Ess from his post on this topic:

Use AI when you need analysis, synthesis, or help in creative thinking.

If your question is a "how," "why," or "what if," then an LLM/AI is a great way to explore or explain. AI is especially good at contextual analysis when you provide the files or information yourself, after you've vetted it.

As Regular Reader Arthur Weiss pointed out, AIs are good for “exploratory queries where there is no single or simple answer and the research may involve a multi-step processes to answer. For such questions, AI wins (backup by checks using conventional approaches).”

They’re also quite good at taking an idea and helping you flesh out some good brainstorming notions that will help you get your writing kickstarted.

The obvious caution applies here: Do NOT let LLMs do your writing for you. If you want to learn anything, you need to be engaged in the content in a deep way. Letting an AI do your writing is like outsourcing the eating of your dessert—sure, it’s more efficient, but you get any of the direct experience yourself?

C. Categories of tasks that LLMs generally do NOT do a good job with: We already talked about how bad AIs are at drawing diagrams. What else do they have difficulty with?

1. Complex Multi-step Logical Reasoning or Novel Problem Solving: Example Question: "If there are three people, Alice, Bob, and Carol. Alice is older than Bob. Carol is younger than Bob. Who is the oldest, and who is the youngest?" (While this specific example might be simple enough for some LLMs, scaling it up to many variables or abstract relationships, or requiring true deductive reasoning they haven't seen before, quickly breaks them.)

Why they struggle: LLMs are pattern matchers. They excel at retrieving and synthesizing information from their training data. When faced with a novel problem that requires breaking it down into logical steps and applying general reasoning principles, they often fail because they don't truly "understand" the underlying logic. They can string together plausible-sounding sentences, but the actual logical is usually absent. (People are working on this, but it’s not quite yet at a believable place.)

2. Providing Real-time, Up-to-the-Minute Information or Future Predictions: As mentioned, current information is NOT the AI strong suit. Example Question: "What were the winning lottery numbers for last night's Mega Millions drawing?" or "What's the latest news on the political situation in <Country X> as of an hour ago?"

Don’t make the mistake of asking an AI for what hours a store is open or when a particular concert will happen—it’s pretty easy for the AI to have out-of-date information.

One study shows that for queries about news, the LLMs can get up to 60% of the facts wrong. (And note that the different LLMs give very different answers.) [CJR article on this]

It's worth knowing this: LLMs have a "knowledge cut-off date." That is, their training data is only as current as the last time they were extensively trained, which can be many months ago. They are often not connected to the live internet in the same way a search engine is, and they cannot predict future events with accuracy. (Again, this is changing—some AIs have live access to the net. But even they’re not super-reliable. But stay tuned, this might well change.)

3. Verifying Facts or Citing Specific, Reliable Sources without Prior Instruction: As you know, LLMs can "hallucinate" information, including fake citations or statistics that sound real but aren't. They don't have an inherent mechanism to verify the factual accuracy of what they generate or to browse and retrieve specific, authenticated sources in real-time. While they can format citations if given the data, they can't reliably find and validate the source material itself without external tools (like Retrieval Augmented Generation, aka RAG). What’s more, I’ve seen a lot of AIs hallucinate citations that look plausible.. but are totally wrong.

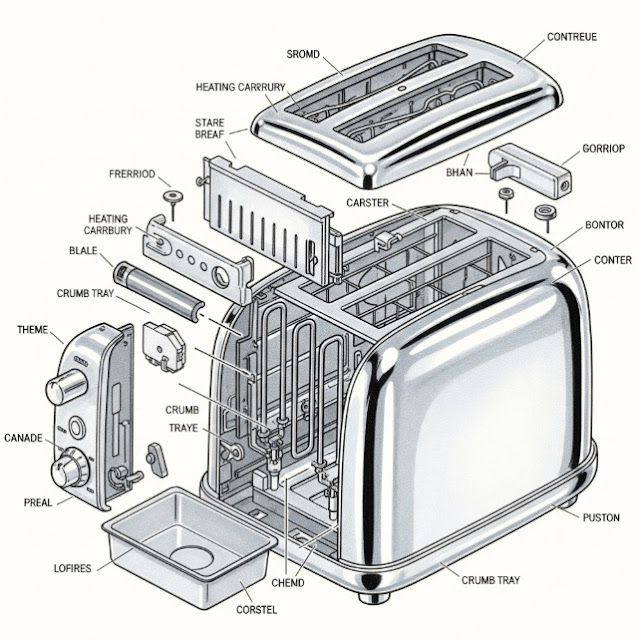

4. Tasks Requiring Fine-Grained Spatial, Physical, or Visual Understanding: Example Task/Question: "Describe how to reassemble this disassembled complex engine part (without a diagram or image input)" or "If I rotate a square 45 degrees clockwise, then flip it horizontally, what will its final orientation be relative to its original position?" Most LLMs will have a tough time with this.

Why they struggle: LLMs process text. They don't have an inherent understanding of 3D space, physical properties, or visual relationships. While they can describe these concepts if the descriptions are in their training data, they cannot perform novel spatial manipulations or truly "visualize" solutions.

5. Delivering Highly Personalized, Empathetic, or Professional Advice in Sensitive Domains: Example Question: "I'm feeling really anxious about my job. What should I do to feel better and address my underlying stress?" or "Given my unique financial situation, how should I invest for retirement?"

Be aware that LLMs lack personal experience, consciousness, and genuine empathy. They don't understand the nuances of a person's emotional state or specific circumstances. While they can offer general advice found in their training data (e.g., "exercise helps anxiety"), they are not qualified professionals and their advice should never be taken as a substitute for human medical, legal, financial, or psychological consultation. Their responses are based on patterns, not true understanding or personal connection.

Bottom line: Basically, LLMs are cybernetic mansplainers—you have to check their work. Bear that in mind as you work through all of this.

Keep searching.. and checking… and searching... .